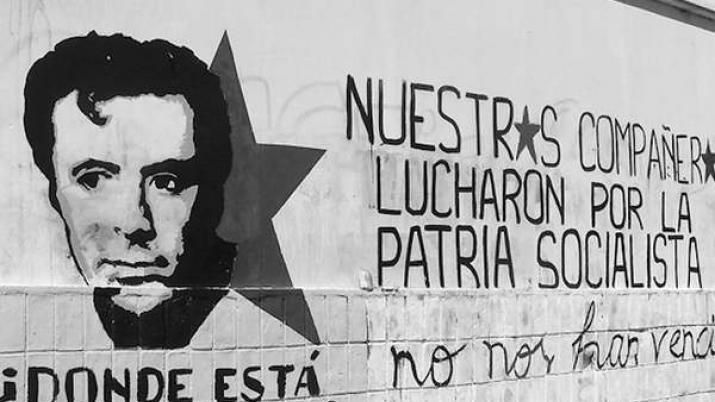

Roberto Santucho and the Fight for Socialism in Argentina - Part I

A political and personal history of one of South America's most important leftist guerilla leaders.

“No one tomorrow can say that we Argentinians were unable to do our duty as revolutionaries and patriots. The new generations, for whose happiness we sacrifice everything, will remember with pride their elders much as we remember the patriots who founded the country.” -Mario Roberto Santucho

Introduction:

Few political figures encapsulate the possibilities, passion and tragic defeat of Argentina’s revolutionary 1970s like Mario Robert Santucho. Known as Robby to his comrades, he was the leading figure of the PRT (Revolutionary Workers Party) and the ERP (People’s Revolutionary Army, armed front of the PRT). Argentina saw the rise of some of the most militant and effective armed leftist organizations over the course of the 1960's and 70's.

While Santucho spent a great deal of time leading a party which was affiliated with the Fourth International, he split from this organization as it turned against guerilla warfare. Within the US and European left there are no major political currents which defend his historical legacy, something which has resulted in an almost total absence of English language scholarship around Santucho and the PRT-ERP.

As one of the great figures of the revolutionary left and one who had a tremendous impact on Latin America his memory deserves to be reconstructed for an international audience. His personal and political history is an inspiring example of revolutionary dedication and serves as a tremendous source of material which we can draw upon to learn from our past defeats.

Early Life:

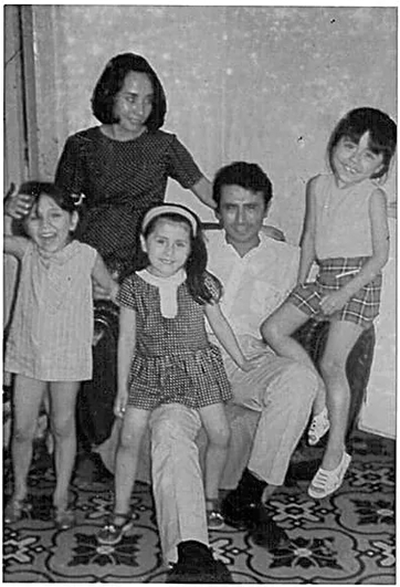

A photo of Santucho's family in Santiago del Estero

Mario Roberto Santucho was born on August 12, 1936 in the city of Santiago del Estero in Northern Argentina. His father was a lawyer and his mother was a schoolteacher. He was part of a large family, his father had 7 children with his first wife and then 3 with his second (the sister of his first wife, who he married after the first wife died). Robby was the oldest of these 3 siblings.

He left home to study in nearby Tucuman, a rural Argentinian province which was dominated by the sugar industry. The sugar plantations and refineries of Tucuman saw brutal working conditions and crushing poverty. Fierce political discussions erupted within the household between him and his brothers.

His first political venture was within the student movement. Through the influence of a magazine in which one of his older brother, Francisco, was a leading participant he became more engaged with the ideas of the left. He was introduced to a wide range of anti-imperialist ideas from Marxism to many of the progressive nationalist ideas of figures like Haye de la Torre. At the university he helped to launch the Independent Movement of Students of the Economic Sciences (MIEC) in 1958, which triumphed in the student elections at the University in 1959. The movement spread to a number of universities in the region and laid the basis for a new organization he formed together with Francisco.

The Indoamerican and Popular Revolutionary Front (FRIP) was established with a base in this student movement as well as links with workers in the sugar industry, coal miners, indigenous villages and agrarian unions. Ideologically it opposed both US capitalism and the Stalinist tradition (in particular the horrendous record of the Argentinian Communist Party). Santucho's older brother Francisco was a key leader in this new organization and as Roberto moved closer to Marxism convincing Francisco was one of the most difficult tasks he faced.

At this point in 1961 Robby married Ana Maria Villareal with whom he traveled across the continent. Over 6 months they visited Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico and the United States. On the return tripped they passed through Cuba, having the luck to be in the Plaza of the Revolution precisely when Fidel Castro proclaimed the socialist character of the Cuban revolution.

Inspired by this experience he committed himself more firmly to the study of Marxism, a study which was combined with the real day to day experience of political struggle alongside the sugar workers. The adoption of Marxism was becoming ever more common under the influence of the Cuban Revolution, and Santucho played a decisive role in moving the FRIP closer to Marxism. A process of joint work and eventual fusion began with the Argentine Trotskyists around Palabra Obrero (Worker's Word), at that time led by Nahuel Moreno. Moreno's group had previously participated in an entryist project in the Peronist movement, a maneuver which was highly questionable in terms of revolutionary principles. As Moreno's group abandoned the entryist strategy, and as the FRIP with Santucho's influence moved every closer to Marxism and Trotskyism, the stage was laid for unification.

The Revolutionary Workers Party

Santucho together with his wife Ana Maria-Villareal and their children in 1967

On May 25th, 1965, the fusion was formalized and the FRIP and Palabra Obrero united to form the PRT (Revolutionary Workers Party).

The political situation in Argentina was accelerating dramatically. Argentina's political regime had previously been under civilian rule, albeit with the most popular party and candidate (Peron) excluded from political life. In 1966 however the military dictatorship of Ongania took power and implemented direct military rule. A broad crackdown on civil liberties began, large numbers of university professors were forced out, and a general process of radicalization accelerated among the student movement. Across Tucuman sugar plantations and refineries began to close which thrusted workers and the region into miserable poverty.

As early as late 1966 the question of armed struggle began to pass from a theoretical to a practical question. However it was not planted initially by a group of students or intellectuals as many of its critics allege. Rather the question of armed struggle was most urgently planted by a number of worker militants in the sugar industry in Tucuman. A series of brutal defeats carried out through the violent assassination of union activists made the question of working class self defense far more urgent.

The death of Che Guevara in Bolivia the following year had a tremendous impact among the Latin American left and greatly impacted both Santucho and the PRT. The debate around armed struggle began to accelerate and a clearer division emerged within the Party. Santucho, most of the party in Tucuman and an increasingly broad cross-section of the national party wanted to proceed to build an armed wing. Moreno insisted on a party oriented towards trade union work. The debate was also complicated by a number of accusations of bureaucratism and “moral” failings against Moreno by leading members of the PRT.

Santucho succeeded in building a national network of supporters within the party and in winning the support of the Trotskyist Fourth International in Paris to his position. By chance, he actually had the good fortune to be in Paris in May of 1968. He was taken to the front-lines by his comrades in the Fourth International, where he was mostly silent due to his lack of French, but later commented with surprise at the lack of violence in the mass actions. His French comrades were quite surprised by this, although their memories may have been colored a bit by later political differences. However for Santucho even if the protests were unexpectedly peaceful by comparison with Argentine conditions, being present in the midst of one of the great uprisings in the heart of imperialism could not help but shift one's view further to the viability of a world socialist revolution. In later years he referred to it as a positive example in favor of revolutionary possibilities within the developed capitalist world.

“The Only Path to Workers Power and Socialism”

Ahead of the fourth congress of the PRT the shifting political strategies came to a head and a definitive split was already set in motion with Moreno. As it became clear that Moreno found himself in the minority, he and his supporters split from the party ahead of the congress and formed a new party, the PRT-La Verdad (which would later become the PST). At the fourth Congress Santucho was the principal author of the central political document that was approved, “The Only Path to Workers Power and Socialism”.

The document outlined a basic economic analysis of Argentina and a declaration of the political traditions upon which the party was founded. It declared both Trotskyism and Maoism to be revolutionary currents of Marxism, aiming for a fusion between them together with the contributions of the Cuban revolution, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

Argentina is defined as a semi-colony of the imperialist countries. The revolutionary struggle will take on the character of a national anti-imperialist war. Anti-imperialist and democratic demands are important especially for winning the support of petty-bourgeois sectors in this stage. However the advances made will provoke increasing foreign intervention which will then strengthen the reactionary forces. This ebb and flow is part of what will give the coming revolutionary war a prolonged character.

Revolutionaries must closely co-ordinate with revolutionary forces throughout Latin America. Imperialist intervention will make it almost impossible for the revolution to triumph alone even for just a short period of time in any one country. This is another reason for the prolonged character of the war and why there can be no rapid victory.

The most revolutionary class in Argentina is the industrial working class, and its allies the urban petty-bourgeois and the poor peasants in the North. The working class in Argentina is beginning to break beyond the limits of Peronism and the control of the union bureaucracy. The vanguard in Argentine and the prime example of this is the working class of the sugar industry and the rural working class of the North.

The polemic with Moreno over the armed struggle takes a central role in the document, a substantial part of which takes on the question of whether the conditions are given for the party to pursue armed struggle.

Santucho argues that Argentina is wracked by a long term economic crisis which the ruling classes do not have a plan to resolve. This sets the background for a serious revolutionary crisis. However the essential component here is the existence of a revolutionary party. Santucho cites Lenin to argue for the position that the armed wing of the party must be prepared in advance of an insurrection, in effect the people's army must be prepared not after, but before power can be taken.

The document also firmly rejects explaining political difficulties and shying away from armed struggle on the basis of a supposed “retreat” among the working class. Instead it points to conditions which will increasingly place pressure on the old ideological structure of the union bureaucracy and the nationalist ideology of Peronism. The document as a whole is marked by confidence in a coming working class radicalization, something for which the party must prepare for and be capable of leading.

Beyond this however it also has an important strategic focus on the rural struggle and a perhaps unrealistic expectation of the possibilities of building a guerilla army in the countryside.

“The struggle of the urban proletariat is fundamental, as it is the driving class of the revolution, however in the current stage of the struggle against imperialism it has no chance of winning if it is not supported by a revolutionary army built strategically in the countryside.”

The argument for this strategic focus on the countryside is primarily the ease with which imperialist armies can intervene in the cities. The Dominican Republic, where the US intervened in 1965, is used as an example. In the view laid out in the document, Latin American governments will increasingly be replaced by dictatorships, which will make defending positions within factories and neighborhoods much more difficult.

The central strategic initiative is the creation of a rural army alongside urban guerilla detachments. In the coming stage the enemy will have an overwhelming advantage in forces, so it is central to keep in mind the defensive character of actions. Northern Argentina will be the key location as that is where the economic crisis in Argentina is most difficult for the bourgeoisie to resolve. To move towards this objective of a rural army the central task facing the party is the construction of a strong and secure illegal apparatus before taking on military actions.

The document is far from representing the entirety of the PRT's political orientation and on a local level views could differ quite sharply. The pressure of political events and mass mobilizations would inject their own life into the theory and strategy of the Argentine Marxists. However the two most important aspects are the recurring themes of an overwhelming confidence in the revolutionary capacities of the working class, as well as a strategic orientation towards a guerilla army based in the countryside.

The practical organization of the armed struggle started from small, less risky operations. A standard military action in the early days would be to ambush a police officer and disarm him, taking his gun to add to the scant military resources of the Party.

What distinguished Santucho from many left leaders and which won him the respect and confidence of so many militants was his absolute commitment to leading from the front. He did not wage a theoretical struggle for armed struggle merely to send others to risk death on the frontlines. Santucho led many of the first armed actions by the PRT, including leading the first bank robbery at the Provincial Bank of Escobar. While the PRT would become famous for far more daring robberies and operations in the future, at the time this was the first serious operation of the PRT and one which provided vital funds to finance propaganda and operations.

The Cordobazo - An Industrial Insurrection

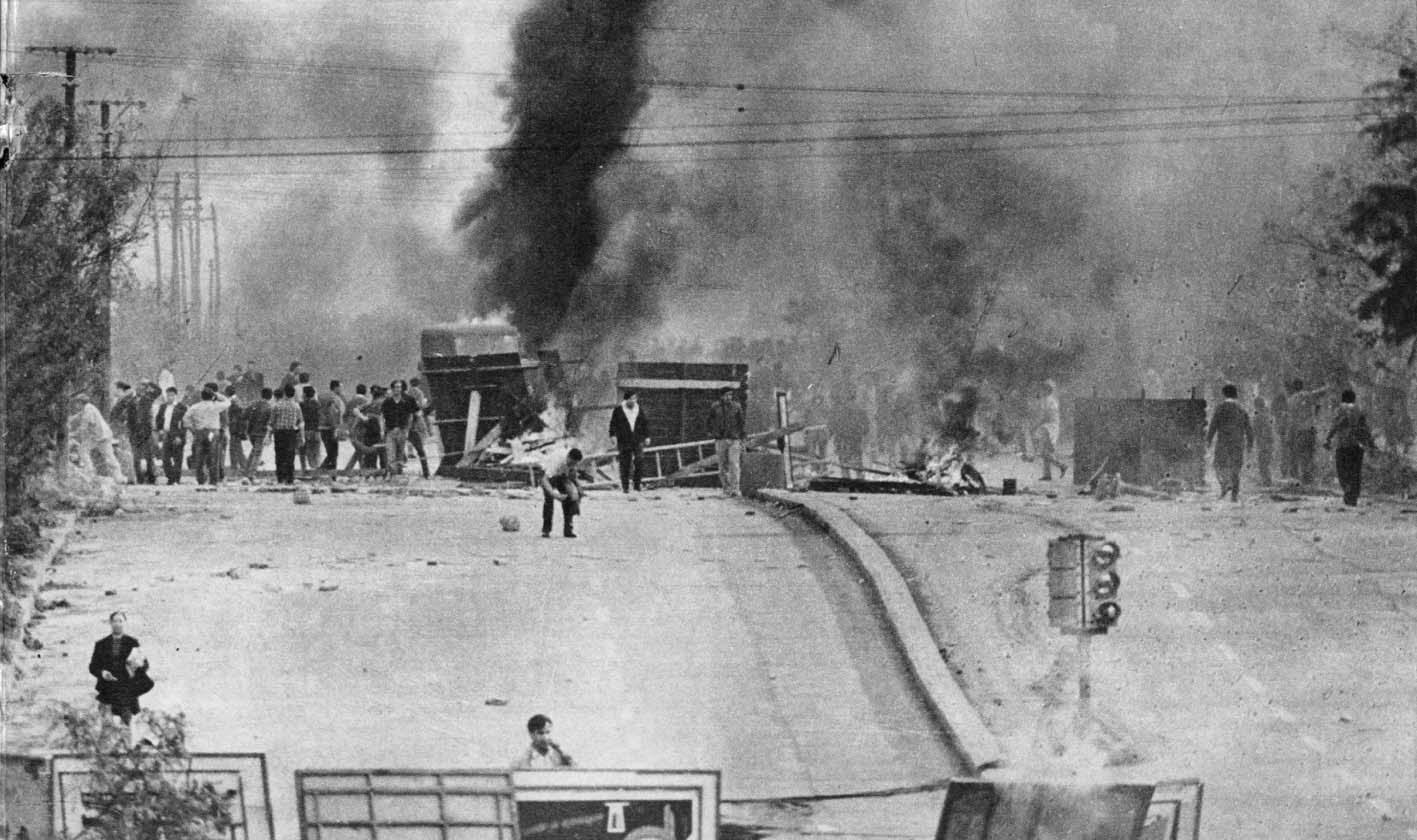

Photo taken of the barricades where police murdered Maximo Mena in Cordoba

The question of armed struggle and insurrection was put directly on the agenda of the left by a mass uprising in the industrial city of Cordoba. Cordoba had a fairly unique political geography. As a city it found itself almost without a proper bourgeoisie — it had experienced a sort of rapid industrialization around some key industries, but it was a city with corporate branches and foreign investments staffed by managers.

It also had an unusually long tradition of student-worker solidarity reaching back several decades. It was a tradition that had been very actively cultivated by a new generation of union and student leaders. Agustin Tosco, the leader of Cordoba's Electrical Power Plant workers (Luz y Fuerza) was a tremendous figure of Argentine working class history. Tosco was an independent Marxist who in his role as a union leader actively cultivated solidarity and collaboration with all working class and left forces around a political aim of overthrowing the dictatorship, and ultimately of achieving socialism. He was a leader who was immensely respected by the working class and he had actively laid the bonds of solidarity and collaboration among students and workers which made resistance on the scale of the Cordobazo possible.

Sparked by an attempt by the government to eliminate a long-standing benefit of half work-days on Saturday, union conflicts escalated into the call for a General Strike on April 29, 1968. The government sought to ban all marches or demonstrations and the stage was set for mass conflict.

The general strike began at 11am Tuesday and was to continue for 37 hours. The plan was for a number of columns of workers and students to converge at the center of the city. Almost immediately after taking the streets however the protesters faced brutal police repression with the aim of repressing the strike. Protesters resisted with stones, barricades and molotov cocktails. At 12:30 a union delegate, Maximo Mena, was shot dead by the police. As news spread throughout the city tens of thousands more poured out into the streets and the tide turned. Protesters instensifed the resistance and militants utilized small arms to push back the police. After 2 hours the Police ran out of tear gas and were forced to abandon the city. As protesters took control, police stations and some foreign businesses were burned to the ground. The city then prepared for the inevitable military intervention by strengthening barricades and cutting power.

The first military troops entered in the late afternoon but advanced slowly through the city. In particular the student neighborhood of Clinicas became a bastion of resistance which lasted throughout the night and the following day. Protesters utilized small arms and rifles to slow the military advance, creating fear among the military of snipers. Only by the end of Friday night, more than a day after the intervention of the military began, was the student neighborhood of Clinicas firmly under military control.

The course of events shook the foundation of the Argentinian regime and played a major part in the process which would ultimately lead to the democratic opening and return of Peron in 1973. An entire city had risen up and no-one could convincingly blame a small band of "subversives" for a city-wide overthrow of the state. For the left, including the PRT and Santucho, it was also largely unexpected and went against many of the expectations they had for the period.

The workers leading the process were some of the best paid workers in Argentina at this time. In particular Agustin Tosco, one of the most important leaders of independent unionism in Cordoba and Argentina, was a leader of the very well paid Power Plant workers union. The spark did not come from the most oppressed, the increasingly unemployed sugar refinery workers that Santucho looked to, but rather a very well situated and well educated sector of the class.

This model of a mass urban insurrection also did not previously fit within the strategic horizon of any of the Left forces. The central PRT document referenced above clearly outlined a rural focus. PRT militants on the ground in Cordoba however played a central role in the events, helping to lead in the frontlines and acting as some of the armed fighters that made the initial victory against the police possible. The fact that the party had been engaging in consistent political work around raising the need for armed struggle and action also helped to create the political environment in which something like the Cordobazo could take place. Yet it is worth noting that the course of events, a mass insurrection which destabilized the national government - emerging out of a movement spearheaded by the industrial working class - was not the course outlined at the PRT convention.

The Cordobazo had a tremendous political impact and in many ways it was far more significant, with more lasting consequences than France's May of 68. However it also posed an important question, having achieved the Cordobazo, what was the next step for the masses? The army retook the city and it's power to achieve this was fairly unquestionable even if heroic streetfighting could delay its victory. An action on the scale of city-wide insurrection inherently poses the question of what can or must a sequel look like. Only it's spread to a national scale (difficult to achieve, perhaps impossible without the co-ordination of a nationwide revolutionary party), or on a local scale it's escalation to not only detaining but defeating the army would represent an advance.

The core division among the Left in the period to follow was between the path of actively carrying out the armed struggle and trying to construct a "people's army", and that of Moreno's followers and some other Trotskyist groups which focused on trade union work and forswore illegal armed actions as "adventurist" or "ultraleft". There were some small groups which charted a mixed path between these two, but they remained isolated and small in comparison to the principle forces on the left.

The political environment created by the Cordobazo helped spur the rapid growth of the PRT. However this same political environment also generated an ever more intense crackdown by the regime on political opposition. The dictatorship aimed to restore stability by making concessions to and entering into negotiations with moderate sections of the Peronists, while attempting to isolate and persecute the more radical Peronists and above all the revolutionary Marxist groups.

In November of 1969 Santucho was arrested and taken from prison to prison until finally left in a central state prison alongside many of the other PRT political prisoners. An initial escape attempt failed, and in the meantime a faction fight within the PRT was intensifying as Santucho's leadership and strategy was questioned by a number of cadre who would go on to form the Revolutionary Workers Group (GOR). This group ultimately split from the PRT shortly before the upcoming conference. After having spent eight months in prison, isolated from many of his comrades and in a difficult position within the Party, Santucho executed an independent plan to escape the prison.

He ingested a pill which provoked symptoms of a hepatitis attack in order to be moved to a state hospital. His wife visited him at the hospital and managed to pass him a pistol she smuggled in. Taking advantage of the lax security during a change of the guard he fled on foot and managed to escape. Almost immediately he set out to participate in the upcoming fifth Congress of the PRT.

The People’s Revolutionary Army

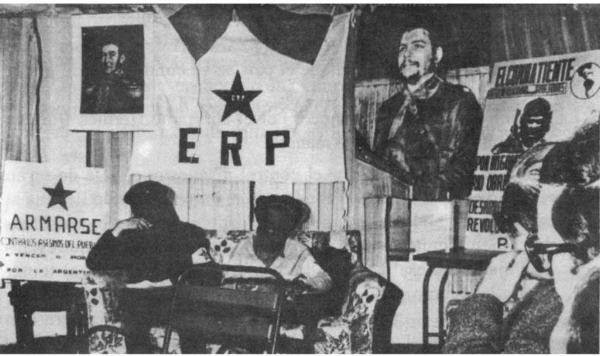

Photo taken of an ERP press conference

In the aftermath of the split, there were fewer than 50 delegates at the 5th Party Congress representing a total of about 150 members. At the 5th Congress the Party voted for the formal creation of the ERP, The People’s Revolutionary Army. The idea was the creation of a military organization which operated more broadly then the party itself.

The discussion at the 5th congress reiterated much of what was laid out in the previously discussed document of the 4th Congress, The Only Path To Workers Power and Socialism. However there were important changes to the general analysis of Argentina and the working class:

"The vanguard sector of the class is composed of the industrial proletariat which is concentrated in Tucuman, Cordoba, Rosario and Buenos Aires. This vanguard is increasingly open to revolutionary ideas. Within this range, the sugar industry workers maintain their place in the vanguard however there is a much smaller difference than in past years due to the extension of the economic and social crisis."

The working class of Cordoba was now clearly seen as being at the vanguard; this would be further recognized by both Santucho and the party newspaper moving to Cordoba and remaining based there for much of the next year. Northern Argentina and the rural proletariat however remain key to Santucho's vision of armed struggle:

"In Tucuman the vanguard sector is composed of the sugar industry workers who are directly linked to the rural proletariat and through them the poor peasants. This, given the geographic situation of Tucuman, makes it so that the strategic focus of the armed struggle will start initially in the form of the rural guerilla. There will be a preparatory stage of tactical and operational actions of urban and suburban armed struggle which will become secondary after launching the rural guerilla. Afterwards this will be extended for all the North geographically, linking areas close to urban centers like Cordoba and Rosario (Santiago Del Estero, Catamarca, Chaco, Formosa, Northern Santa Fe, etc.)"

This strategic focus for Northern Argentina would remain central up until the more or less decisive defeat of the PRT-ERP. Urban armed actions would be principally aimed at liberating money, supplies and weaponry to support the project of a guerilla army in the mountainous North. Several detachments were eventually created precisely with this goal of first establishing, and then later linking up liberated zones across the North.

The document as a whole also cites far more frequently references to Vietnam than it does the Cuban example. This parallel with Vietnam would be a consistent theme and a consistent problem for Santucho and the PRT. Accusations against Santucho of "Focoism" are largely misplaced and both he and the party criticized Focoism substantially. However this consistent "Vietnamization" of the struggle, the expectation that the class struggle will unfold in Argentina in a way similar to that of the independence process in Vietnam, was a recurring theme and ultimately a serious weakness in Santucho's strategy for the PRT-ERP.

Argentina is considered to be in the midst of a "revolutionary civil war", one which has already started and for which the left must rapidly organize its forces and actively lead the armed struggle. However this does not imply an abandonment or de-prioritization of mass work and union work, on the contrary this is to be given the highest priority.

Internationally the party retains it's links to Mandel's Fourth International although it simultaneously maintains strong critiques, finding itself more in line with Cuba and wanting to be very open to collaboration with non-Trotskyist organizations like the Chilean MIR and Uruguayan Tupamaros.

The key proposal of the conference is the formal foundation of the People's Revolutionary Army, the ERP. The ERP is defined as a military organization which is open to forces broader than the party itself but which acts under the PRT's political leadership. The first tasks of the PRT and of the newly born ERP will be a series of small but well publicized armed actions which will establish it as a serious, revolutionary alternative.

Escalating the Struggle

Scene from Sere Milliones, a film which recreated the ERP's most famous robbery

After the conference the organization went ahead with planning some of the first armed actions to expropriate funds, seize weaponry and make the ERP well known as one of the major guerilla forces in Argentina. The ERP was formally announced after a botched operation resulted in a shoot-out in which two police were killed. The number of actions escalated rapidly from expropriating printing equipment to sophisticated bank robberies. While repression from the state was significant, new recruits quickly replaced those who fell and the organization continued to grow in size and influence.

During this period Santucho was elected as the formal military chief of the ERP. In March of 1971 there was a repeat of the Cordobazo, this time with ERP flags and banners appearing alongside other guerilla organizations like the Montoneros in the frontlines of the street battles. By mid 1971 the ERP was claiming responsibility for more actions than any other Argentine guerilla group, and it took an audacious step with the kidnapping of a high profile British manager of the Swift corporation.

Even with the responsibilites of leadership, Santucho risked himself in frontline operations. In June of 1971 he organized and participated in the liberation of PRT-ERP prisoners from the womens prison of Buen Pastor near Rosario. Those liberated included his wife, and accounts from militants remember him having entered the prison disguised as a priest to help clear the way for the escape.

In July Santucho was invited to join Cuban celebrations of the anniversary of the attack on the Moncada Barracks. He also found himself more openly in dispute with the leadership of the Fourth international, which was retreating from it's previous positions in favor of guerilla warfare as a strategy for Latin America.

While in Cuba Santucho met personally with a number of high level military leaders, including Arnaldo Ochoa (who was then of course still highly regarded). He also strengthened ties with the Chilean MIR, Uruguayan Tupamaros and the Bolivian ELN, pushing for greater international co-operation which would become evident in the joint statement they released a few years later. The impending break with the Fourth International meant that reconstructing international ties became much more urgent, a reconstruction which also involved softening criticism of Stalinism in line with the Cuban government's own adaptations to greater reliance upon the Soviet Union.

When Santucho returned to Argentina, the stage was set for a political break with Mandel. Luis Mattini, a leading militant of the PRT-ERP, left a record of the final meeting between Santucho and the French representative of Mandel's Fourth International:

"The environment for the French delegate was hostile despite the fact that Santucho clearly held an enormous respect for and paid a great deal of attention to the guest. Santucho patiently listened to the reports and the harsh criticisms of the militarism, empiricism and practical compromises of the PRT... Santucho criticized the United States Trotskyists for not supporting the struggle of the Black Panthers who, in his judgment, would be at the vanguard of the revolutionaries in the United States. Sandor responded declaring that it was very evident that there were neither objective nor subjective conditions to start the armed struggle in the United States. The discussion ended with a comment from Santucho which left many of the members present there uncomfortable: "It is not a question of conditions, but rather a problem of political line"."

Mattini's own later political evolution mean his accounts must be taken somewhat critically, however the content of the debate is particularly interesting. Santucho's reference to the Black Panthers shows his strategic vision was not limited to Latin America. Even if the Panthers also met a tragic fate at the hands of overwhelming state repression, it is a historically valid criticism of the Trotskyist movement and the US SWP.

A few weeks after returning to Argentina, on August 31st 1971, Santucho was arrested in Cordoba shortly after meeting with representatives of the other major guerilla organizations in Argentina. Upon his arrest he was beaten and tortured with the electrical prod - the favorite tool of the military and police interrogators.

Imprisonment and Isolation:

Imprisonment again made the process of leading the PRT-ERP incredibly difficult. The political situation was changing rapidly as the dictatorship began to set in motion the foundations of a new election. Peronism would be legalized, and potentially the left could even participate legally in the coming campaign. The party had to develop a political line capable of intervening effectively in this new environment and Santucho, trapped under state surveillance, found himself with a minority position in the organization.

In the first letter he was able to write to his wife, later in September, he elaborated on the isolation they faced within the Prison.

"In regard to the guys I don't have contact with any of them. Our situation is extremely isolated and rigorous, we can only talk with the guards. Those who were captured with me I see every 2 or 3 days for an instant without being able to exchange anything more than a salute"

His wife was among those who were firmly against any participation in the elections. While Santucho was prepared for the possibility of an undemocratic election which would justify a boycott, he also wanted the PRT to be open to participation under the right conditions:

"The adoption of one or another tactic should be taken in the next few months and will depend on the level of democratic concessions that the dictatorship will grant. More fundamentally it depends on the attitude of the masses. If we opt for the boycott, this should be an active boycott. If we opt for participation we should take this on from a principled position, a proletarian position, to emphasize the political independence of the proletariat and try to have this be a pole for other popular sectors, under the clear hegemony of the working class."

The political difficulties resulting from Santucho's detention were compounded by the overall repression unleashed against the PRT. While the ERP was growing as an organization many of the long term leading cadre of the Party were being either imprisoned or disappeared.

Meanwhile the guerilla struggle continued to escalate rapidly as the Military government attempted to step back from the democratic process. Peron responded by giving further support to the Peronist guerilla organizations, which created a political opening for the far left. Polls revealed that approximately 45% of those in the capital of Buenos Aires supported the guerilla struggle, and this approached 50% in the countryside.

The ERP like the Montoneros, FAR and other guerilla organizations enjoyed enormous popular support and were able to use this to recruit new members and achieve spectacular actions. In what became known as the "Robbery of the Century", ERP militants occupied the National Development Bank and seized over 10 million dollars which went on to finance the revolutionary struggle.

Another major but ultimately unsuccessful action was the kidnapping of Oberdan Sallustro, a leading manager for FIAT. The President of Fiat flew in from Italy to negotiate for his release and personally met with Santucho (against the wishes of the Argentine Government) to this end. Two accounts exist of the negotiations, one from Santucho's lawyer in which an accord was reached and the government moved Santucho immediately to prevent this. The second by ERP militant Luis Mattini is that there was no agreement as Santucho insisted on liberty for political prisoners that only the government could achieve. What is certain is that Santucho was transferred almost immediately after the negotiations, and shortly after during a police raid on the hideout Sallustro was shot dead.

Santucho was transferred to the maximum security prison of Rawson in the far south of Patagonia. When he found out about the impending transfer, he apparently had a short conversation with the union leader Agustin Tosco:

"Hey Gringo, how many kilometers is it from the prison at Rawson to the nearest airport?"

"Don't even think about it, it's impossible to escape from there, not even with a Russian submarine."

Escape from Trelew:

At Trelew the Argentine Dictatorship held most of the leading guerillas who were captured legally (rather than executed extrajudicially, a fate which awaited many). As well as the leadership of the ERP, the leadership of the FAR (of Maoist origins) and a few high level cadre of the Montoneros were concentrated together. Agustin Tosco the union leader who played such a key role in the Cordobazo was also transferred there in the aftermath of a new wave of worker resistance in Cordoba. The military unintentionally created the groundwork for signficant exchanges of ideas, joint study and discussion groups among the imprisoned guerillas.

An audacious escape attempt would also became the first example of a joint operation to unite the ERP, FAR and Montoneros.

The prison had approximately 70 guards, of whom about half were armed. Three blocks from the prison there was a military base with an anti-guerilla company of 120 men. 20km away was a Naval Airforce base with more than 1200 men. The group inside the prison depended on one real handgun and about 10 replicas made from wood and soap.

The first signal would come from outside the prison, upon receiving this Santucho would say "Now" and remove his sweater to signal the start of the operation. Marcos Osatinsky, the one prisoner with a real gun, moved towards the front and killed one of the guards who attempted to block the escape. The prisoners acted quickly and took control of the prison with no other casualties.

Upon exiting the prison however the operation faced the first major problem. The trucks which had been secured to carry the 114 chosen prisoners weren't there, the militants in charge of the trucks left after hearing the gunfire assuming the operation had failed. What was left was a single car for some of the maximum leaders, including Santucho for the ERP and Quieto for the FAR.

They were followed by 19 more who attempted to organize an escape with a few taxis and cars that were brought in. Meanwhile the first car arrived at the airport and with one of the escapees disguised as a military officer they succeeded in boarding, and then taking control of the BAC One-Eleven plane which they had planned on using to transport everyone. They waited a few minutes in case any of the other escapees could show up and then took off.

The 19 arrived late after a delay along the road with the plane already in the air. Seeing that escape was now impossible, they set about doing everything in their power to create a media spectacle so that they would be taken into custody alive rather than killed by the military. They succeeded in creating a stand-off long enough to secure a peaceful surrender.

The plane succeeded in touching down in Allende's Chile, where it immediately set off a diplomatic crisis. The MIR and sections of the Chilean socialist party protested in defense of the guerillas and aimed to ensure they could pass safely to Cuba. The Argentinian government and the Chilean right wanted them extradited as terrorists.

Meanwhile in Argentina, at 3:30am August 22nd, the 19 prisoners captured at the airport were led out of their cells at the Airforce base where they were being kept. They were ordered to lay down and they were then gunned down by two military officers. The official story claimed another escape plan, however it was clear to the world that what happened was a planned political execution. Among those murdered was Santucho's wife, Ana Maria Villareal.

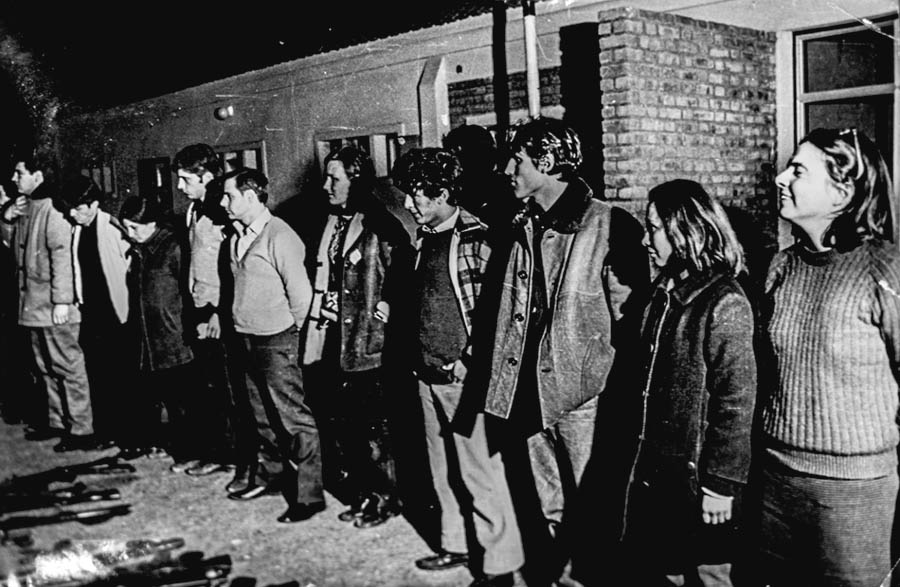

A photo taken of the captured militants shortly before the Massacre

The escaped prisoners and Santucho learned of the massacre while they were still being detained in Chile. A lawyer related the scene when they found out:

"Everyone was in a large room on the first floor, with bars on the windows and a big table. Some were just stopped. I remember that Robby [Santucho] was at the head of this table. I told them that there had been a massacre of the prisoners and read out the names of the dead. The more impulsive ones... shouted and cursed. Robby crossed his arms over the table, held his head and stayed like that for more than two hours. He didn't say a single word. He stayed petrified while the room was filled with shouting. It was a heartrending scene and still today I don't know what was more moving: the weeping and the shouting, or the petrified silence of Santucho."

Across Argentina protests erupted alongside armed actions, including the bombing of government buildings. A 14 hour general strike was declared. The massacre received broad international condemnation and played an important role in further discrediting the military government in advance of the elections.

Allende promised to send them on to Cuba on three conditions: That Peron condemn the massacre, that major political parties and the CGT (the major Argentine Union) condemn the massacre, and finally that the Argentine military uniform that they had be turned over. The conditions were met and everything was set in place for the escaped guerillas to continue their journey on to Cuba.

Before leaving, Santucho recieved a visit from Beatriz Allende, the President's daughter. She related the conversation while she was in exile in Cuba before her suicide in 1977.

Beatriz: "My father sends you his pistol, to defend yourself with it. I'm very sorry for what happened to your partner. My father says that in Chile he does not share the path you have chosen, but you should never forget to be faithful to your ideas. He sends you a hug"

Santucho: "Thank you. Tell your father that I respect his honesty and his courage. I wish for the Chilean people to defeat the reactionaries and imperialism. We will defend Chile wherever we can."

With a pistol gifted from Salvador Allende and the key to the prison from which they fled as a gift for Fidel Castro, Santucho and the escaped guerillas finally set out for Cuba. For the ERP, Santucho and the rest of Argentina's armed left however the greatest period of political convulsion was yet to come. The coming elections, the return of Peron and an unprecedented explosion of class struggle set the stage for the left to rise to spectacular new heights before its tragic defeat.